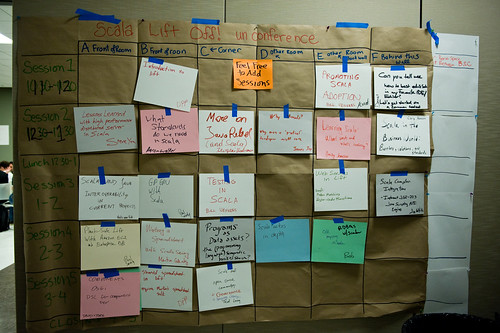

I stayed around in San Francisco for one more day after JavaOne, in order to attend the Scala liftoff. The liftoff was an open space style conference (which has a more specific meaning than “unconference”, at least to me). My friend Kaliya Hamlin did a great job of facilitating the day.

Scala has steadily been gaining attention, and hasn’t yet hit (at least in my eyes) the hype part of the classic Gartner hype cycle. I’ve been poking about with Scala, mostly because of the type inferencing, the Actor library, and lift. I have great respect for the work that Martin Odersky has done over the years, which also has me interested. Couple that with what I learned about closures in Java at JavaOne, and the list of reasons to look more deeply at Scala is getting long, especially if you are determined to have a statically typed languages.

I wasn’t able to make it to any of sessions on lift. It just worked out that other sessions overlapped them in a pathological way. While this is unfortunate, I am sure that I’ll be able to pick up anything that I need from the mailing lists and other documentation. I was able to attend two sessions on actors. One of the sessions had people with questions about actors, but no Scala actor experts were in that group. There was some discussion of Pi-calculus and the join calculus, but no discussion of the actual actor theory.

Steve Yen’s session on actor-d was pretty useful. Steve set out to build a version of memcached using Scala’s actors. He spent most of his slot talking about Scala/Java isms that he ran into – this was important since he was comparing to the C memcached. By the time he got to the actor related stuff, he was almost out of time. Steve found that he had to remove actors from the main loop of his server in order to get sufficient performance. He wanted to get statistics from the server in the background and discovered that he main loop actor was always processing messages and was never idle long enough to report statistics. He ended up replacing the actor with plain old Java Threads (POJT?). This was in addition to all the fact that he ran into many of the standard Java problems as well. I’m not sure what to conclude from this. I don’t recall what kind of hardware he was on, and I am not convinced that he had the right architecture for an actor based system. Some of his experience also seemed contrary to what the lift folks have been claiming. I think that we are in for a decent amount of investigation here. One of Martin’s statements about Scala is that it is possible (and better) to extend the language via libraries than via actual language constructs. For the most part, I agree with this, but there are certain extensions which have interactions with the runtime – like concurrency. In those cases, I don’t see how the library approach allows taking advantage of runtime features. The current version of Scala actors is implemented as a library.

One of the things that I am currently working on is support for Python in NetBeans, so I dropped into the session on IDE support for Scala. With the exception of IntelliJ, none of the IDE plugin principals were present, so it was hard to have a really productive discussion. Martin did attend the session and we talked about the possibiliy of getting hooks into the existing Scala compiler, particularly the parser and the type inferencer. That could yield some big dividends for people working on IDE support. One IDE feature that I would like to see is the ability to hit a key, and have the IDE “light up” all the inferred types, overlaid on the existing program code. This would allow developers to see if their intuition about the types actually matched that of the type inferencer. I’d like a feature like this for Python/Ruby/Groovy/Javascript code as well. Further discussion was deferred to the scala-tools mailing list.

The other session that I participated in was the session on Scala community and governance. Several people wondered about this during Kaliya’s “What questions do you have about Scala” portion of the schedule building. When nobody else put up a session in this area, I grabbed a slot, hoping to spur some conversation – if for no other reason than my own education. Fortunately, Martin had already been thinking about the problem. He is going to adopt a Python style governance, with him (and EPFL) having the final say on language design matters. There will be Scala Enhancement Proposals (SEPs), like the Python PEPs. I’m very happy with this. I think that Python has done very well at maintaining the balance between (lots) of community input on the language design, while still retaining that “quality without a name”. One of the things that I said during the CommunityOne general session panel was that particular individuals in the right place, at the right time, matter at great deal. After watching Martin for the day, and seeing his interactions on the mailing list over the last few months, I think that the design of Scala is in very good hands.

We also talked about the evolution of the Scala libraries. The Scalax project is working to build a set of utility libraries for Scala. Martin views scalax as a place where anyone can submit a library, have it tested, vetted, reworked, etc. Eventually some code in scalax would be candidates for addition to the Scala standard libraries. This also seems like a sane approach to me. I like the idea of having a place for libraries to shakeout before going into the standard libraries. Martin also mentioned a LINQ in Scala project. I need to track that one down too.

It is good to be in a multi-language world again. There’s room for Scala, Python, Ruby, and others. Another language that I am keeping my eye on is Newspeak.